|

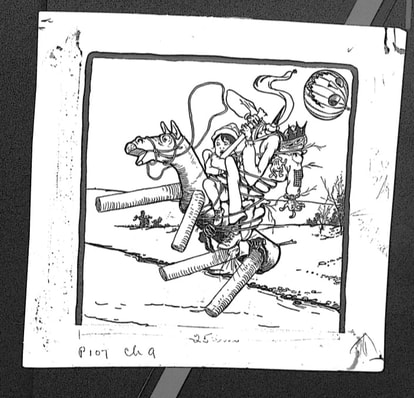

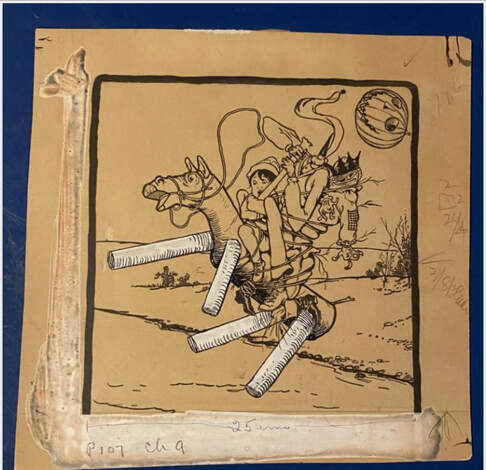

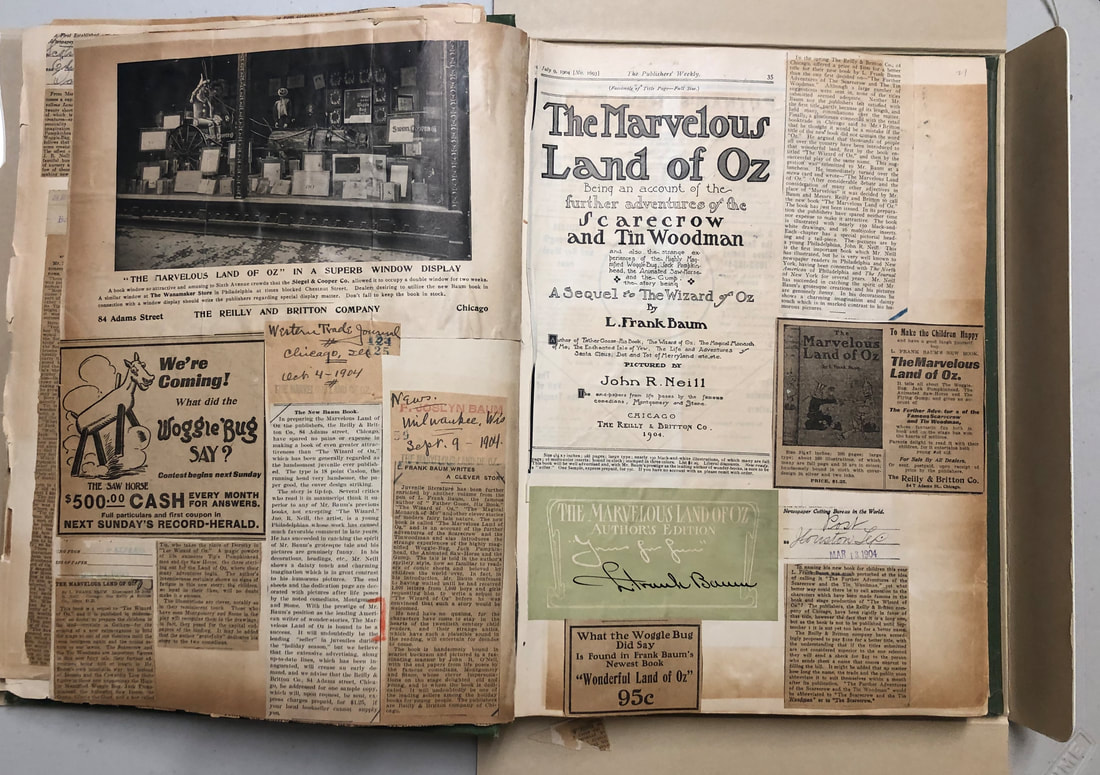

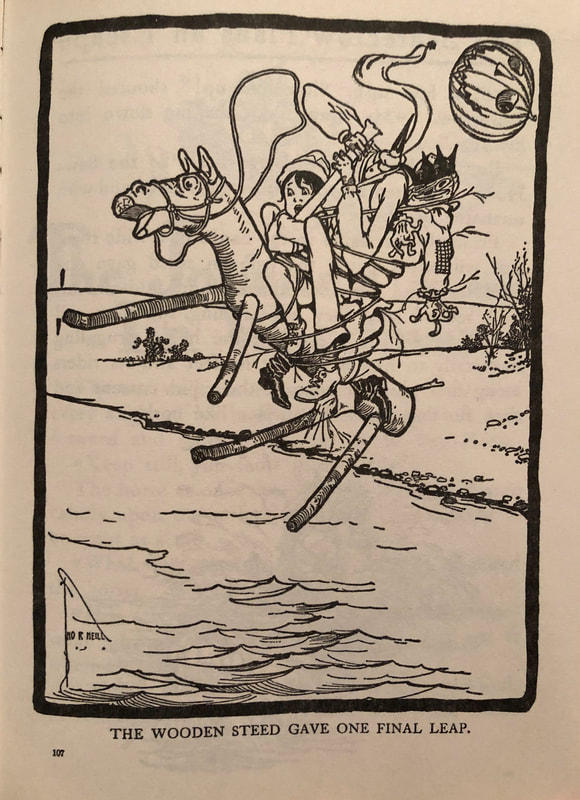

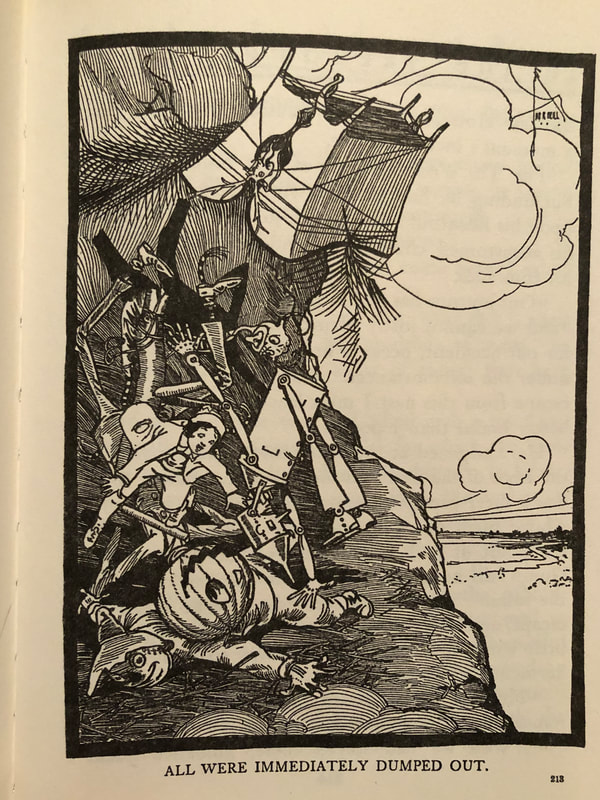

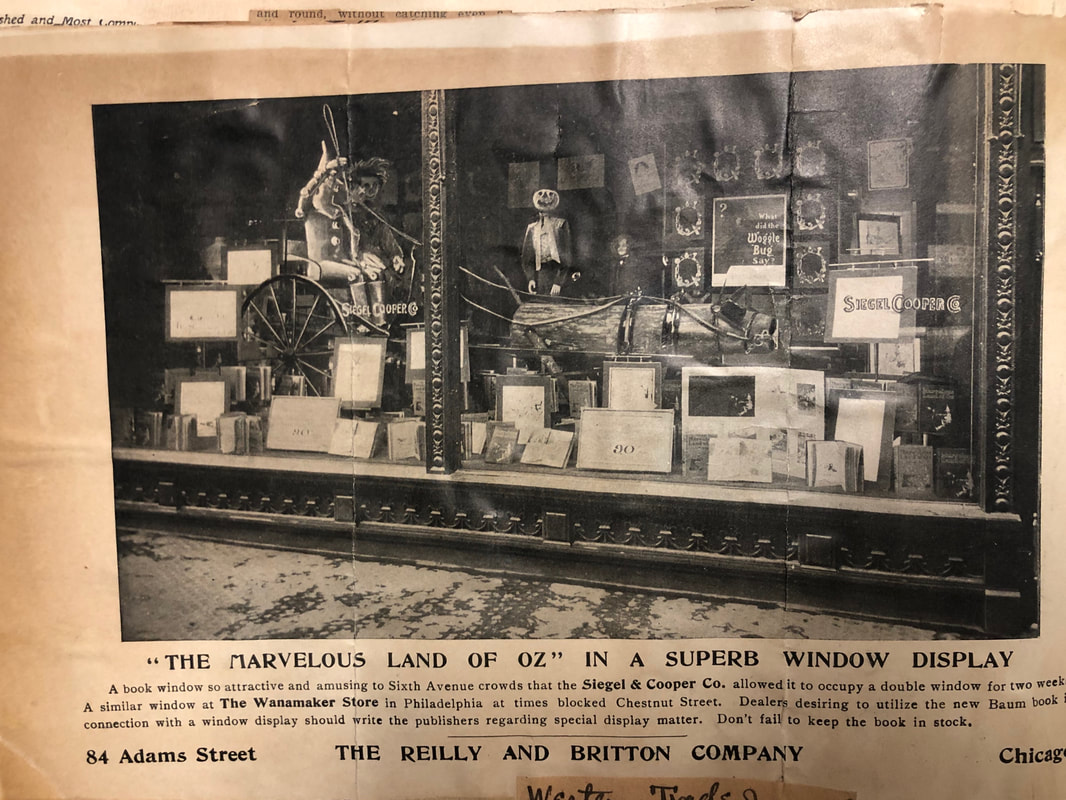

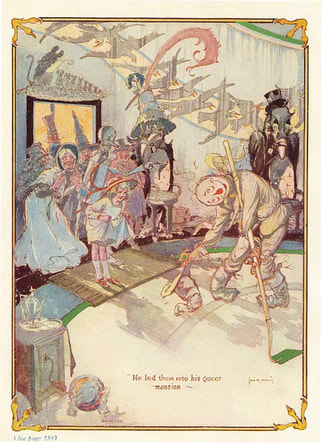

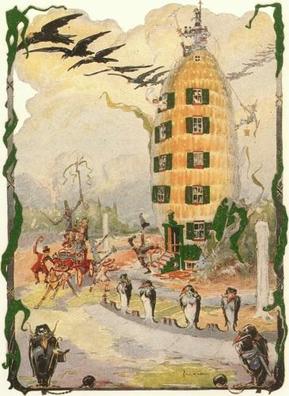

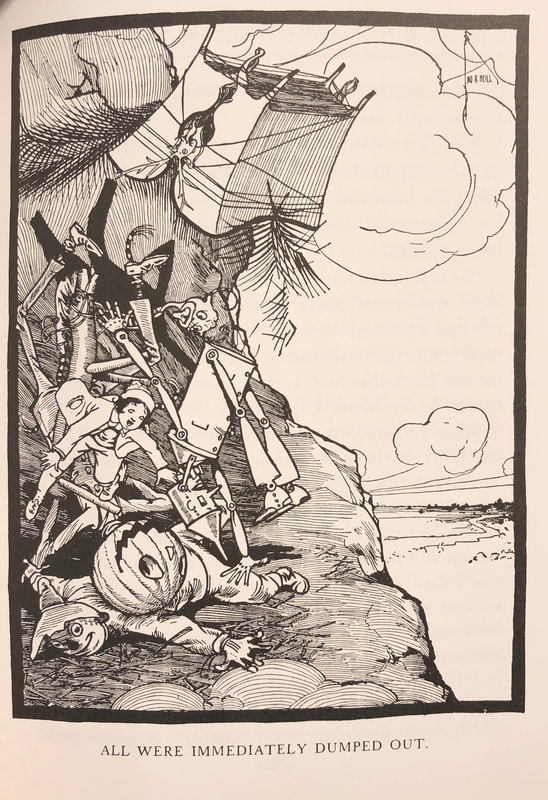

As originally printed in 1904, two John R. Neill illustrations for The Marvelous Land of Oz On the quest to uncover the surviving original artwork drawn for the Oz book series, The Marvelous Land of Oz remains tantalizing. Published four years after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, this first Oz sequel was an enormous success in 1904. Surviving photographs pasted in L. Frank Baum’s personal family scrapbooks reveal not only the extensive advertising blitz that surrounded the book’s release, but that the original pen and ink artwork drawn by John R. Neill to generate the illustrations in the book were showcased in elaborate promotional displays in department store windows. The handful of surviving artworks from Land are also some of the earliest found in private collections. Oz author, Jack Snow was one of the first major collectors to seek out original illustration boards from the Oz books, which hitherto had mostly been considered just utilitarian parts of the printing process. But faced with financial hardship, Snow sold the bulk of his Oz collection to rare book dealer Howard S. Mott, who in quick turn re-sold three pieces to Columbia University in 1955. In an earlier blog, The Lost Art of Oz examines one of these illustration boards in the Columbia archives that is an anomaly: an original pen and ink drawing that correlates to a drawing in The Marvelous Land of Oz, but that is resized and eliminates the central character of the Wogglebug from the illustration. A recent discovery at the University of Virginia offered a similarly intriguing variant. Described in the school’s library catalogue as an original pen and ink drawing by John R. Neill, published with the caption "The Wood Steed Gave One Final Leap,” a xeroxed file copy provided by the library staff revealed some eyebrow-raising irregularities. The illustration itself is cut - nearly by a third- and more quizzically, the legs of the Sawhorse crudely redrawn to be thicker than in the drawing as it appears in the book.  Could this, indeed, be John R. Neill’s original pen and ink board from 1904? If so, why the alterations? And would Neill himself have been the one making the changes to his own work? Luckily, a spirited investigation by Penny White, reference librarian at UVA, along with insightful findings by the incomparable ‘Royal Researcher of Oz,” Michael Patrick Hearn provides us with some answers - not only about the drawing at UVA, but as it turns out, also the mystery illustration at Columbia. In 1918, the George Matthew Adams Service, a prominent newspaper syndicate offered a serialization of The Marvelous Land of Oz in weekly installments, under the title “The Wonderful Stories of Oz.” Archival images of newspaper sheets reveal that both variant drawings were, in fact, reprinted in the Adams Service feature. Taking into account the needs and specifications of recreating an image on a newspaper page, alterations, like the truncations made to the original "The Wood Steed Gave One Final Leap" illustration, begin to make sense. To a lesser degree too, it’s easy to imagine why certain details, like the legs of the sawhorse, might be changed to be more visible when printed as a smaller image. But if the mystery about ‘what’ the modified illustrations were intended for was finally solved, other questions remained. Were these revised drawings Neill’s original artwork, and would he really have done such modifications himself? As it turns out, in both instances, the answer is likely no.  Closer examination (and scanning) of the drawing at UVA reveals that the image in their library is, in all probability, a modified printer’s proof, with the revised horse legs drawn over corrective paint. Oftentimes, proofs are also retouched by hand with dark ink, so it’s not unusual for them to be mistakenly identified and catalogued as an original pen and ink drawing, even by experienced researchers. In contrast, the drawing at Columbia is, indeed, an actual pen and ink drawing, but when we take into account the obstacle of resizing the original illustration in the book from horizontal to square, it seems the illustration may have simply been redrawn to fit the specifications for newsprint.  As for Neill potentially drawing the revised illustration himself, while the image is a close copy, Neill’s grand-daughter, Jory Mason, herself an accomplished artist, is quick to point out, “In my opinion, the illustration does not look like his line work." The revision also lack’s Neill’s signature from the original - likely another tell-tale sign it was instead the work of a skilled in-house artist emulating Neill’s style. But perhaps most persuasively, there is no record, either in the publisher’s files or Neill’s family papers of Neill ever having been paid to modify any of his illustrations for the Oz book series - either by redrawing them (or in the instance of other found works - by embellishing pen and ink drawings with watercolor to make them more suitable for advertising re-purpose). Lest we forget, for much of Neill’s career, illustrating the Oz books was simply ‘a gig’ - one of many that the industrious Neill took on each month in his career as a working illustrator. It’s unlikely he would have taken on the extra assignment without further compensation. Neill, after all, had no idea in 1904 or 1918 of what “Oz” would eventually come to mean as an enduring, decades long American phenom... Only in 1941 - decades later - did Neill write, “I’m beginning, after about 40 years,” to realize there is more to this Oz stuff than I thought.” As it would happen, the line was written to Jack Snow, who would end up adding a faux drawing to his own collection, perhaps one of the first prized as a Neill original. Special thanks to Michael Patrick Hearn, Jory Mason, Penny White, and the University of Virginia for their expertise.

1 Comment

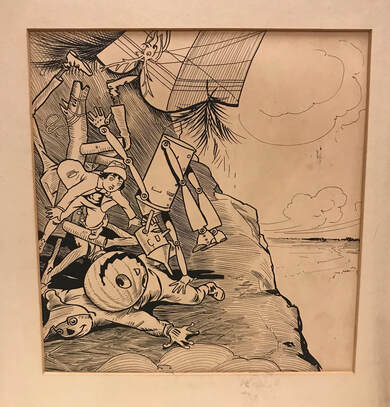

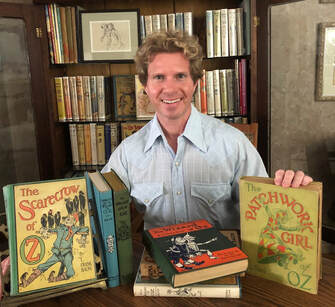

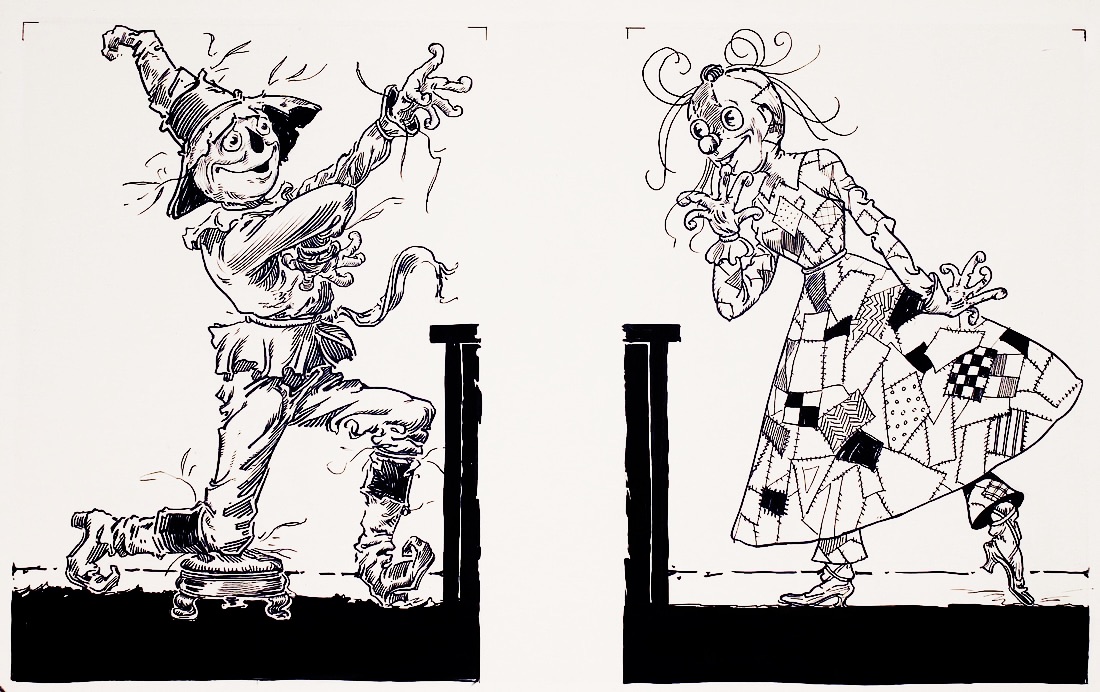

The following story was first published in the Spring 2020 edition of The Baum Bugle, the journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club. If you aren't yet a member, what are you waiting for? When I launched the “Lost Art of Oz” project in the fall of 2018, my first goal was to make a list of all the original illustrations known to survive. That continuing journey began with a “deep dive” through auction brochures, sales records, and library catalogues. Even more instrumental were the remembrances and expertise of keen collectors. Over the years, many had informally made notes about the current whereabouts of that art, much of it drawn over a century ago by master illustrators John R. Neill and W.W. Denslow. The search quickly revealed that most of the surviving original Oz drawings by Neill have one of two origins: they are either those saved through the preservation efforts of collectors, Fred Meyer, Lucy Hart, Irene Fisher, and most significantly Dick Martin in the late 1950s, or they are the last of the drawings still owned by publisher Reilly & Lee when the firm was sold to the Henry Regnery Company in 1959. This second group was sold by Peter Glassman of Books of Wonder in the early 1980s, and all the art has been subject to a myriad of changing hands in the succeeding decades. As a result, the discovery of a major “new” piece—its survival hitherto unknown—always raises excitement about the possibility of future discoveries. One such treasure was found in 2016 by collector and Oz Enthusiast blogger, Bill Campbell. Bill is an artist and a lifelong Oz fan. His focus has always been on collecting the original books and artwork from the series. As Bill remembers: “I have a general habit, after arriving home from work, of browsing through eBay and looking at searches related to my various Oz interests. On this occasion, I had barely started looking when an illustration popped up at an attractive ‘Buy it Now’ price. I recognized it immediately as a double page spread of Scraps and the Scarecrow drawn by John R. Neill for The Patchwork Girl of Oz. After a moment of being a bit stunned to see it, I realized I’d have to act quickly. It appeared to have just been listed, and I knew it wouldn’t be available for long! “My partner, Irwin, was upstairs. With a shout of, ‘We’re spending money!’ I ran up with the iPad to show him the drawing. His response was simply, ‘Make sure it’s what you think it is!’

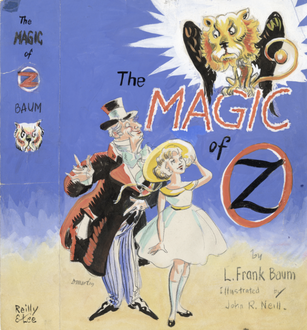

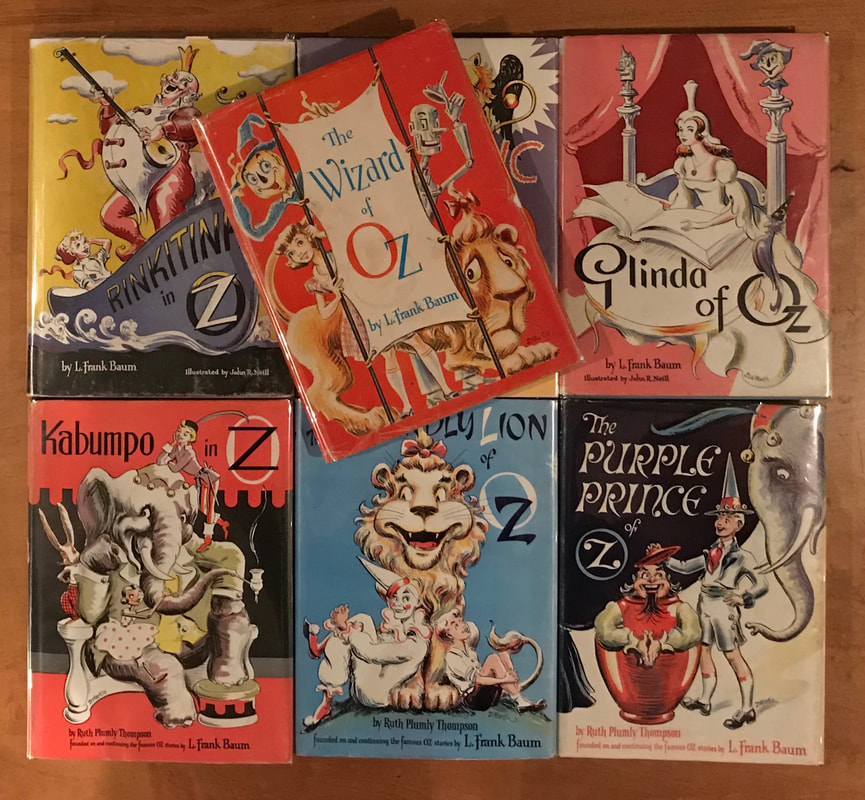

After a quick second look, I crossed my fingers and made the purchase. It was sold by an older gentleman somewhere on the east coast, possibly Rhode Island. I ended up speaking to him over the phone to arrange shipping, but I could learn nothing more about where the drawing had come from. Apparently, he didn’t have any others. He didn’t seem to be an Oz collector. When the piece arrived a week or so later, it was immediately obvious that it was the real deal. As always, it was a joy taking in Neill’s artistry. Though it was printed in color in the book, the original drawing is crafted solely in pen and ink. The scale of Neill’s Oz work is very impressive, with the drawing measuring a good 13” tall by 22” wide. This increase in size over the printed version in the book makes the artist’s pen work and graceful line all the more impressive. Neill’s artwork in the Oz series was a major part of why I fell in love with the books as a child, and it’s always a thrill to see an original example. Another lucky stroke: Neill drew many of his early double paged drawings on separate boards, but for whatever reason, he opted here to draw the Scarecrow and Scraps together. Truly an inseparable duo! The board also had a strong odor of old cigarette smoke. But after allowing it to air out for another week or two, it went to the framer. It has been beloved on our wall ever since.” Much of the original Neill artwork for The Patchwork Girl of Oz is known to survive, yet many of the most prominent illustrations are still at large. The discovery of such a significant piece spurs the imagination: who might have had it for the past 100 years? Could a former employee of Reilly & Lee have brought it home? Did a store clerk keep it from a window display? We may never solve the mystery, but we can dream that more Oz treasures are out there just waiting to be found. The Palos Verdes Verdes Pulse has published a new article about "The Lost Art of Oz" and founder, Brady Schwind's ongoing search. Full text below!  For over a century, The Wizard of Oz has been America’s best loved fairy tale, and from almost the very beginning, Los Angeles has played an indelible part in the story’s enduring legacy. Oz’s Chicago based author, L. Frank Baum, found Southern California’s beaches irresistible, and yearly winter pilgrimages to the coast fueled his imagination - and inspiration - for stories that delight children of all ages to this day. My love affair with Dorothy and her fantastical journey down the yellow brick road began, like it does for so many, as a young child watching the classic MGM film. Shot in Culver City on soundstages filled with Technicolor visions (and a pitch perfect performance by Judy Garland), the movie remains as timeless and wondrous as it was in 1939. When I hit grade school, I excitedly discovered that before the movie, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a book. And that the book had a LOT of sequels! Discovering that my great-grandmother had antique copies of the Oz books from her childhood turned me into an instant collector. Along with Baum’s whimsical writing, I especially adored pouring over the books’ fantastic drawings. The series’ illustrators, led chiefly by W.W. Denslow and John R. Neill had the gift of making Oz seem at once like a place beyond my wildest dreams: but so real in its depictions, I wouldn’t be surprised to see one of its wonderful creatures standing on a local doorstep. When I was presented with the opportunity to acquire a few original drawings used to create the illustrations for the Oz books for my collection, it was a dream come true. What I didn’t realize was how rare the artwork actually was. For the Oz series (written between 1900-1960) nearly 4,000 original drawings were penned to illustrate the books. The work was done mostly ‘for hire’ for the books’ Chicago publisher, Reilly & Lee, but by the time the company did an inventory of their archive in 1983, there were only a few dozen pieces left. What could have happened to it? Where could all this magnificent and creative art so vital to my childhood have gone? I simply had to find out, and in the fall of 2018, the “Lost Art of Oz” project was launched. The scavenger hunt to find and catalogue the surviving original artwork has since taken me around the world to visit libraries, universities, antiquarian book dealers, and private collectors, everywhere from Dallas to New York to Minneapolis to London. One particular challenge has been that the artists didn’t sign much of their work; if you are only familiar with the world of Oz and its characters as they appear in the 1939 film, you might not recognize the first depictions of the story. The search has also been one of identification and preservation. Often, when found, the illustration boards are damaged or incorrectly labeled. Pieces have turned up not only at the Library of Congress but at swap meets and on eBay, so the hunt has required a wide net of exploration. It was a common practice in the early 1900s to send the original artwork out to be used for promotion and window displays. It wasn’t always returned, and this has led to artwork being discovered in some quite unexpected places. A handful of the series' beautiful watercolor paintings turned up - thirty years after they were loaned for a book display - in the basement of Marshall Fields! Of course, as irony would have it, the greatest spoils I’ve found by far have been in California - the land so close to Baum’s own heart. Once I began to dig, like a hidden trunk unlocked, treasures unfurled. A film scholar in San Pedro had a drawing she had purchased at a Wizard of Oz convention as a child. A book dealer south of LAX showcased a drawing he'd bought at auction and had lovingly restored. And a chance phone call from a coastal gentleman revealed a trove of extraordinary drawings that hadn’t been seen in decades. Where the artifacts have ended up over the past century has been as varied and unpredictable as the people who ended up with them -- but what all these collectors seem to share is a deep affection and attachment to what this fairy tale means, both at the personal level and to our American culture. Like Dorothy on her journey, the quest has also led me to an extraordinary band of allies: scholars, experts and friends eager to share and be a part of the continued discovery. Perhaps most meaningful of all are those who don’t own art but who call simply to share Oz books they loved from their own childhood, or valuable copies excitedly rediscovered in an attic from their own family’s past. As if to signal the timelessness and universal appeal of the story, last summer, the El Segundo Museum of Art (ESMoA) launched the wildly popular “Experience 31: Oz.” The exhibit lovingly brought together what might be the largest amount of Oz artwork ever assembled in a traditional museum setting. As it turns out, the loss of all that artwork reflects art history. The art of Oz was lost because at the time it was created, it wasn’t valued. Of course, few could have anticipated that one hundred years later, a simple children’s book would have become such an ineffable part of our heritage. Finding and sharing the artwork, especially with those who’ve never had the chance to see the illustrators’ works in person, is my continual joy -- and like all great adventure stories, the quest goes forward. With each new drawing I rediscover, I’m reminded of the message that lies at the center of The Wizard of Oz itself: in our search, heart, brains and courage will always lead us on the path back ‘home.’ Do you have vintage books, artwork, or memorabilia related to The Wizard of Oz? If so, The Lost Art of Oz project would love to hear from you. Visit them on the web at www.lostartofoz.com and follow them on Facebook and Instagram.  Brady Schwind is an award winning writer, director and performer who has called Palos Verdes home for nearly two decades. While his life long journey as a storyteller has seen him traverse stages from Hollywood to New York, Brady’s passion for one particular enduring children’s classic has recently taken him on a story book adventure of a different kind. In his search to uncover “The Lost Art of Oz”, Brady finds himself returning ‘home’ and to the story’s local California roots. The International Wizard of Oz Club is featuring a recurring column contributed by 'The Lost Art of Oz.' in their publication, The Baum Bugle. The following first appeared in the Winter 2019 edition.  Dick Martin in the late 1950s. Dick Martin in the late 1950s. Roughly 4,000 illustrations were created for the canonical "Famous Forty" Oz books, perhaps the most popular and best-selling American children’s series of the early 20th century. By my approximation, less than ten percent of the final original artwork drawn by W. W. Denslow, John R. Neill, Frank Kramer, ‘Dirk,’ and Dick Martin for the series is known to survive (367 pieces, as of this writing, if you want to be succinct). My journey to discover how most of this artwork disappeared—almost all of it created, ‘for hire,’ for the publisher, Reilly & Britton (later Reilly & Lee)—led, in the fall of 2018, to the creation of my online project, The Lost Art of Oz. In my eagerness to quell personal curiosity, catalogue the surviving original illustrations, and hopefully pave the way for more Oz artwork to be found, I should have guessed Baum and his illustrative collaborators, even from the great beyond, would weave a cosmic quest of adventure. The riddle of what became of this artwork would reveal its own fables of mind, heart, and moxie. The journey would also lead to a lesson in the evolution of what constitutes "art" and the reality that by the time it is usually recognized as such, much of the physical artform has already gone by the wayside. Most of all, I would discover the brilliance of a series of men—drafters, painters, skechers, fine line masters—who never considered themselves "artists." These were American illustrators, whose individual and collective imaginations helped lay the foundation of a pop culture phenomenon that lives on—and continues to build on—their imaginations a century later. The first three decades of the 20th Century marked the heyday of "Ozmania," but by the late 1950s, Reilly & Lee was floundering. Artist and lifelong Oz fan Dick Martin went to work for the publisher in 1957; with little offered monetarily, Martin reportedly often worked for the company in trade, bartering his artistic services for compensation with treasures out of the Reilly & Lee archives. Among those treasures were all the finished illustrations John R. Neill had drawn for the Oz books—or what was left of them. By the late 1950s, the Reilly & Lee archives were largely in tatters. Years of building moves, neglect, and lax lending (and unofficial borrowing) had left Neill’s collection of original artwork, drawn in pen and ink on bulky Bristol board, both spotty and spotted. In 1959, Reilly & Lee was sold to Regnery Publishing. When it was discovered that most of the original Neill "key art" required to reprint the series’ cover and jacket designs was missing, Roland Roycraft, art director for Regnery’s advertising agency, Kencliffe, Breslich & Company, was enlisted to redraw the covers to match Neill’s art. After sampling Roycraft’s reconstructions, Henry Regnery decided a more contemporary look might better serve Oz in the mid century, and Roycraft was instead directed to create new bold, cartoonish covers (perhaps befitting a youth culture being weaned on Howdy Doody and Huckleberry Hound). Facing a public who thought Oz increasingly pasee, as well as solidifying condemnation from vocal detractors in the public library system who, for decades, had banned the Oz series, Regnery quickly made an about-face and realized that his greatest hope to save the languishing Oz series was to position them as American classics. Dick Martin, whose traditional artistic aesthetic blended 1950s homespun Americana with the whimsy of John R. Neill and the comic strip accessibility of W.W. Denslow, suddenly found himself, at last, in the Oz spotlight. In 1960, Martin not only illustrated The Visitors from Oz, a new adaptation of Baum’s 1904 newspaper strip, "Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz," he also drew new dust jacket designs for ten volumes of the classic series.

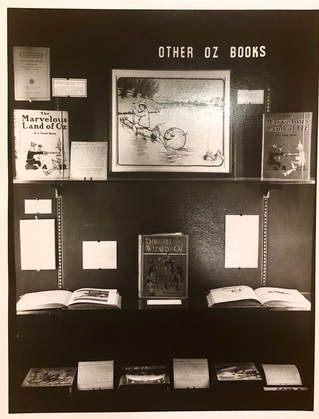

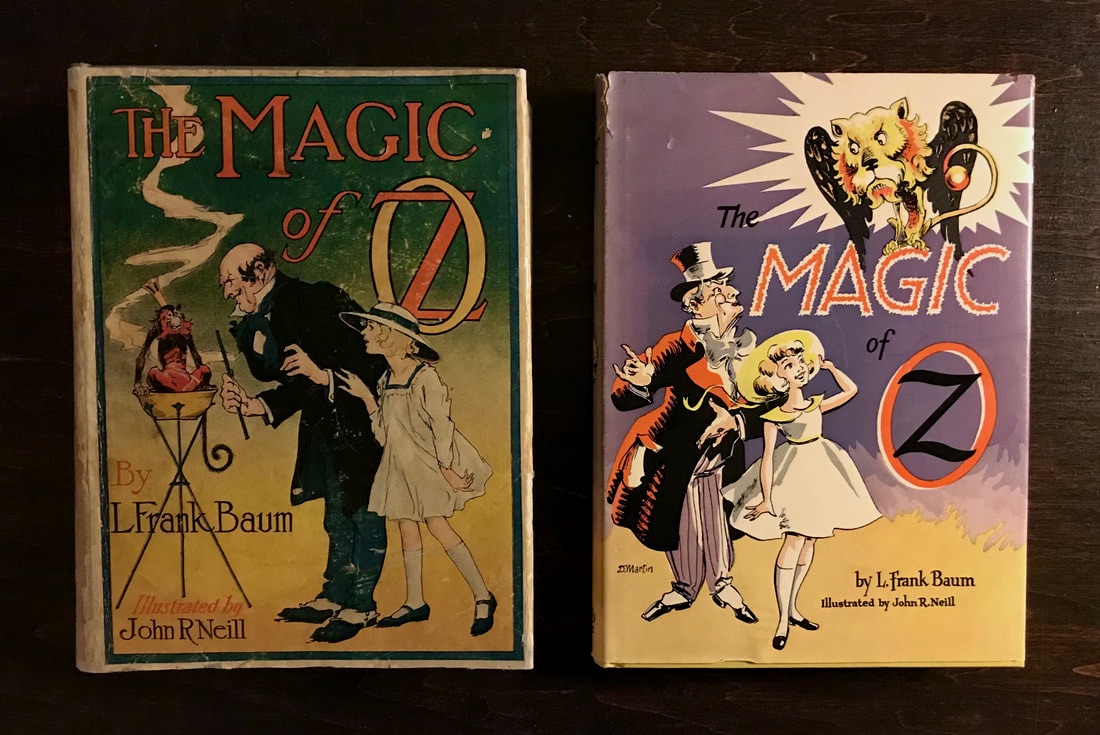

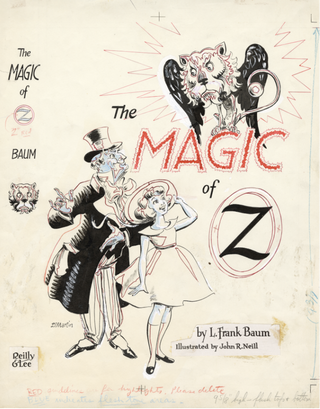

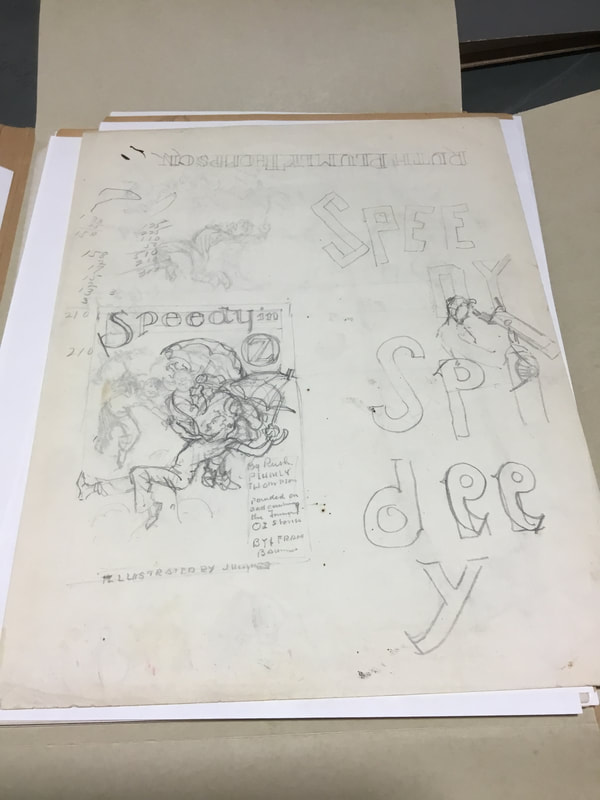

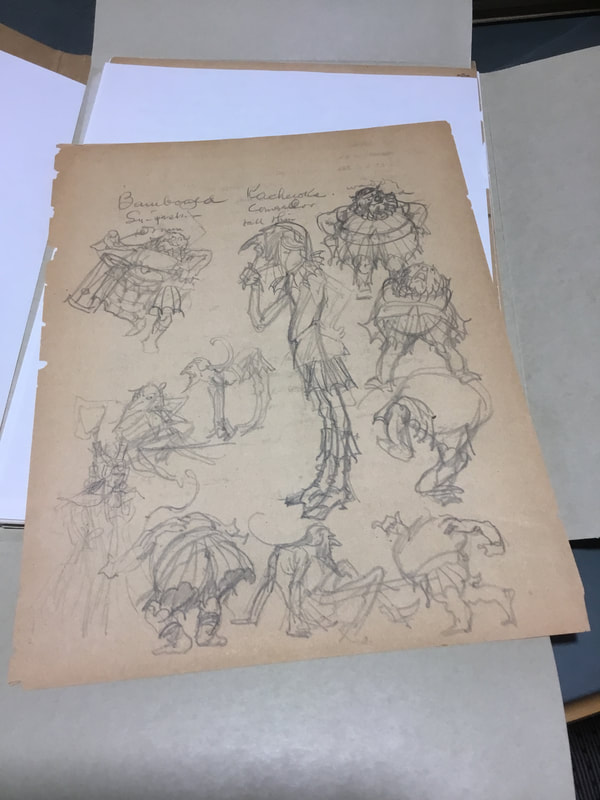

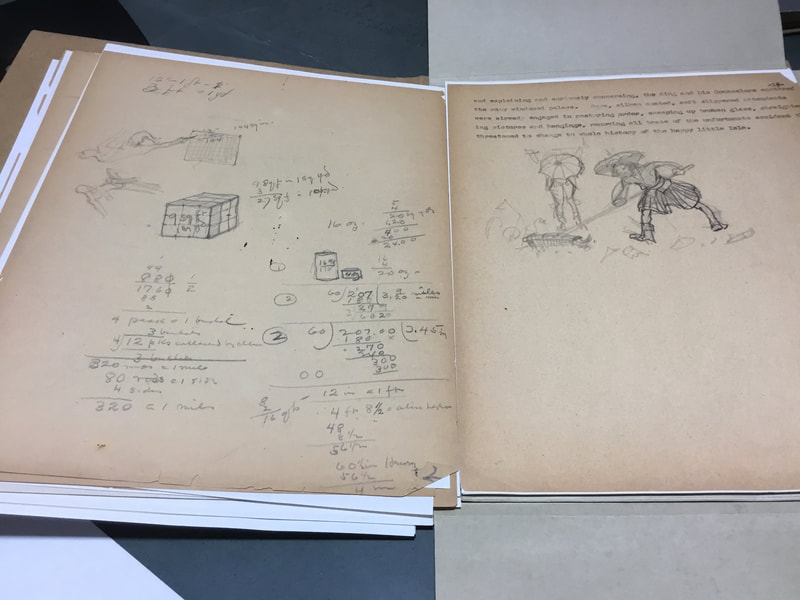

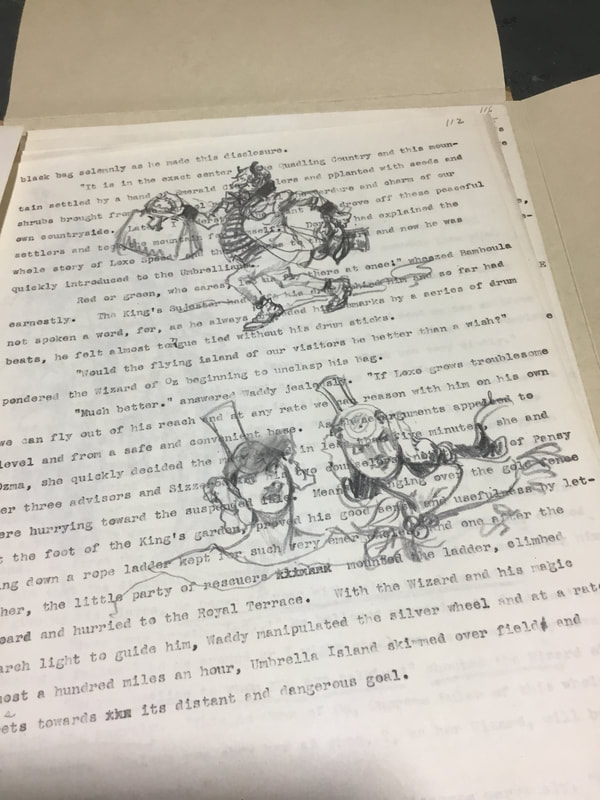

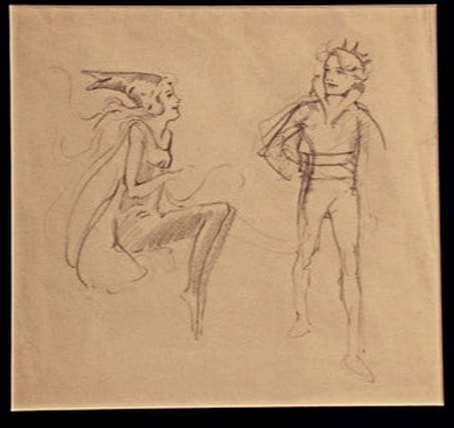

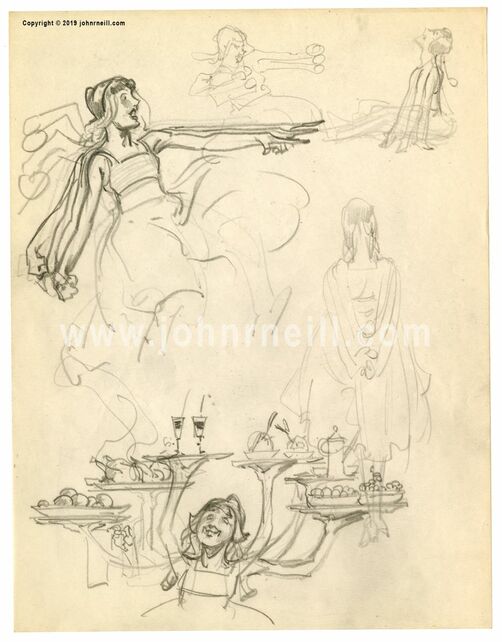

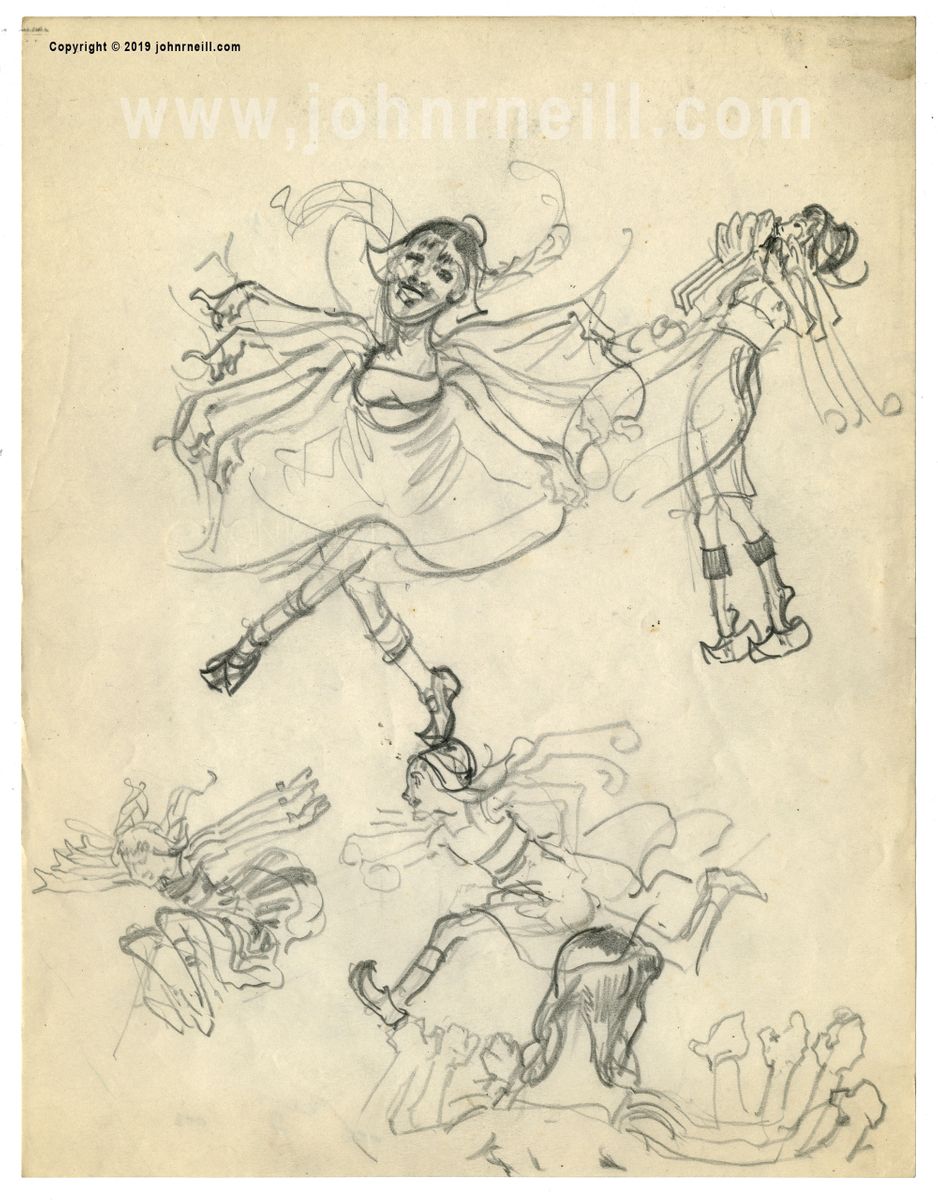

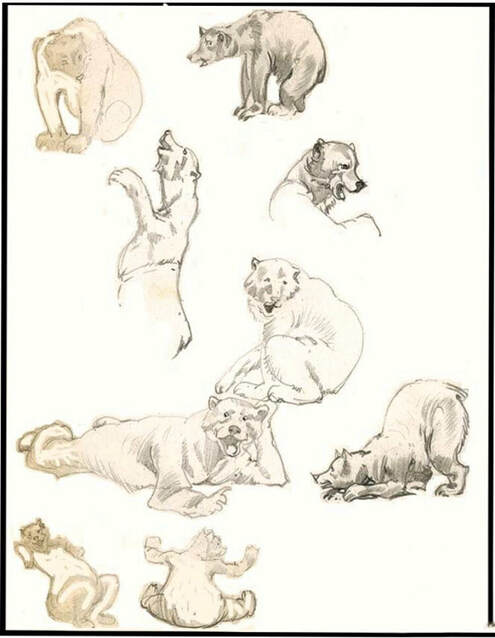

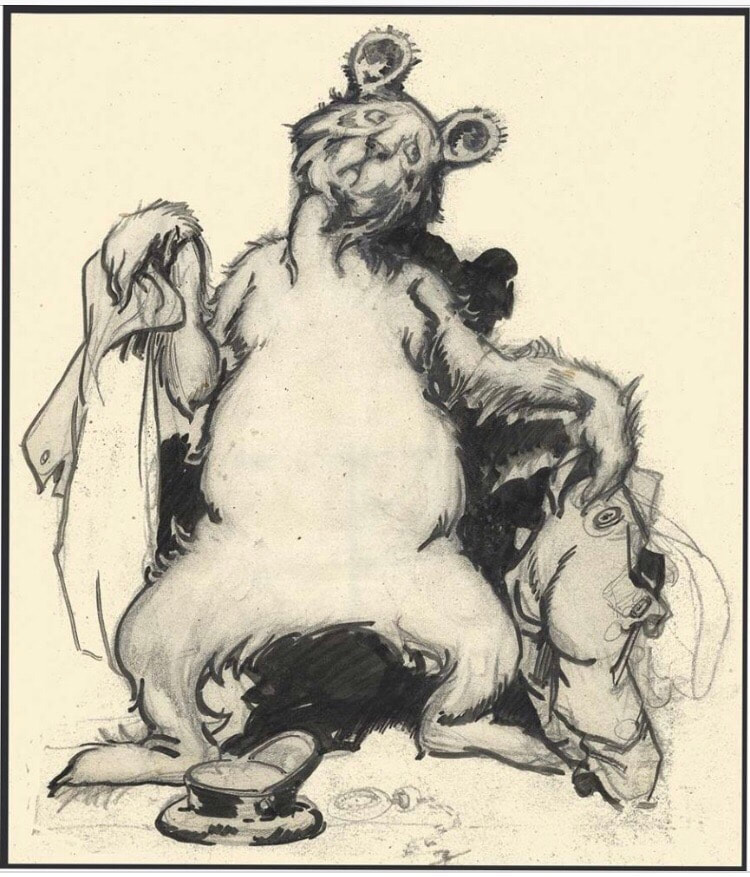

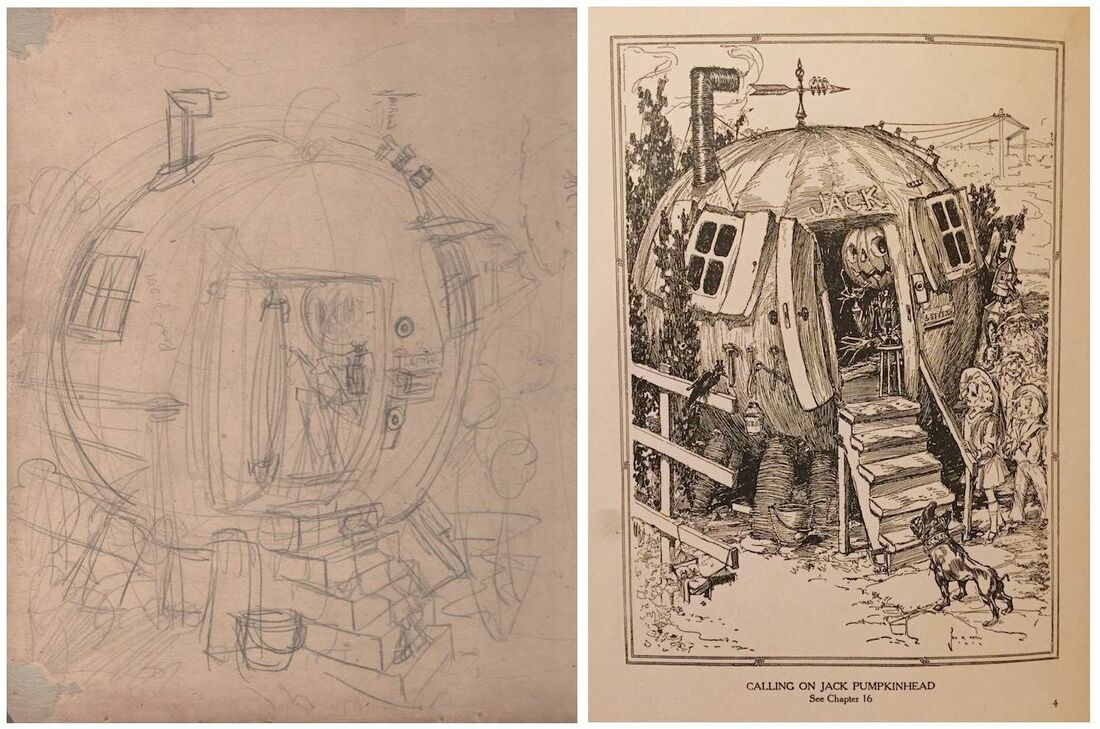

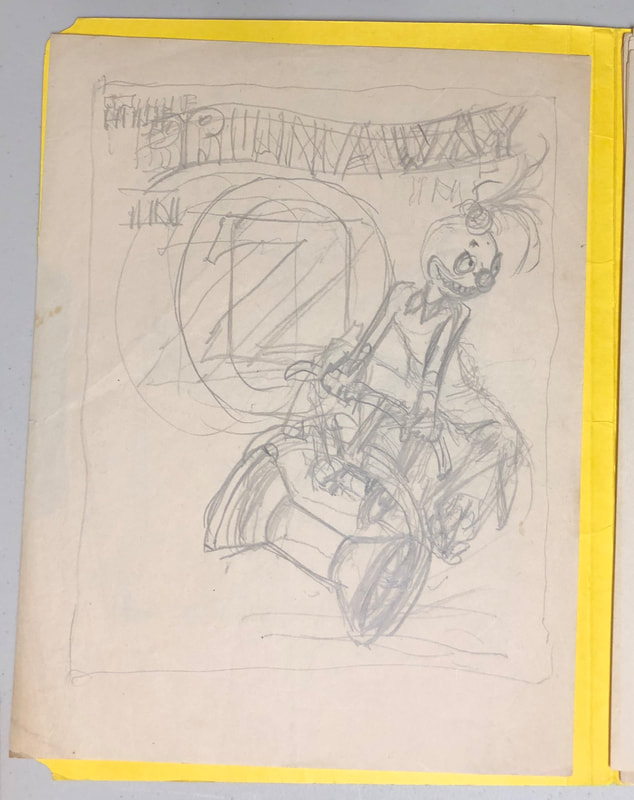

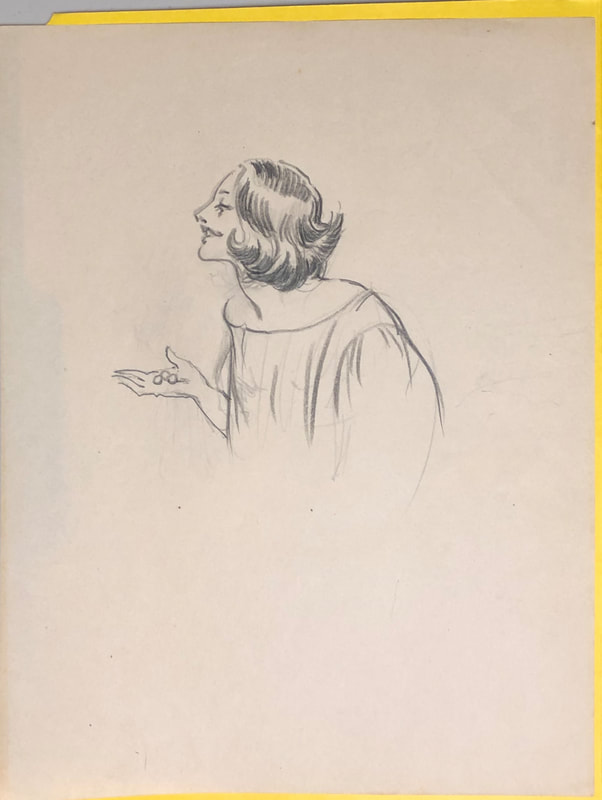

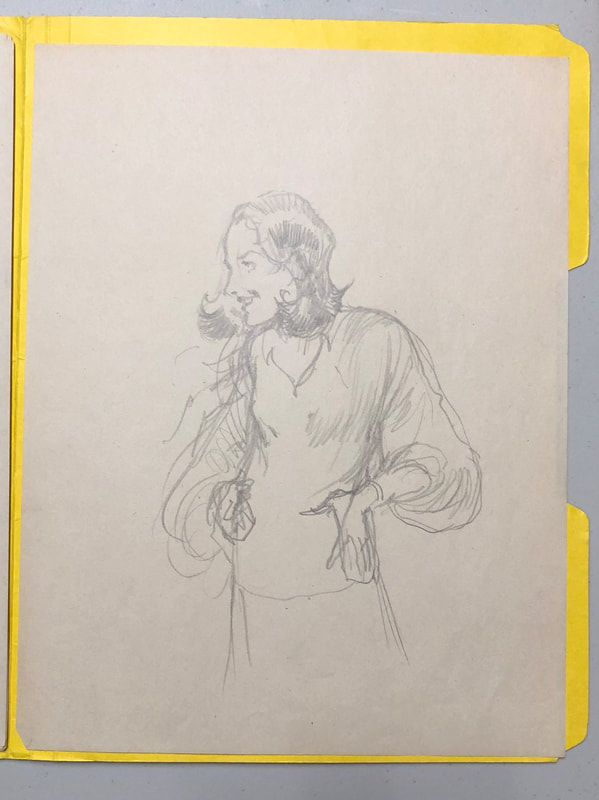

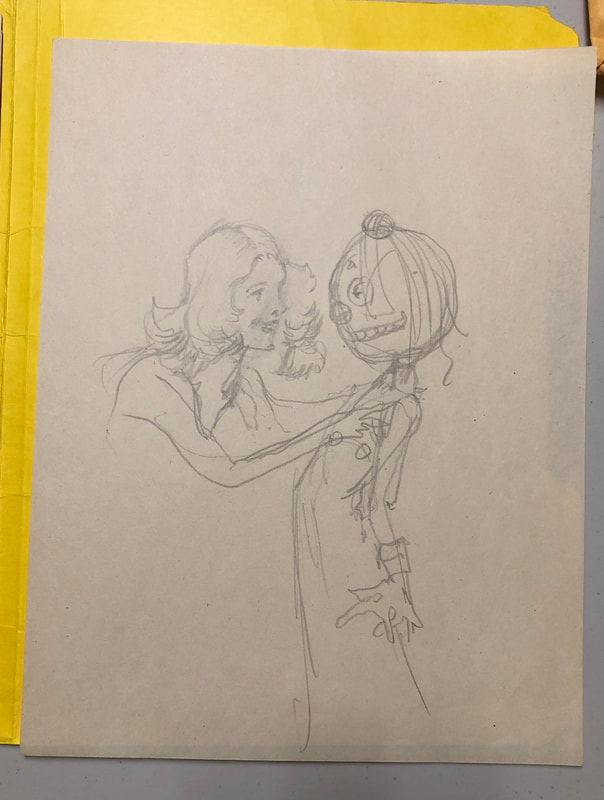

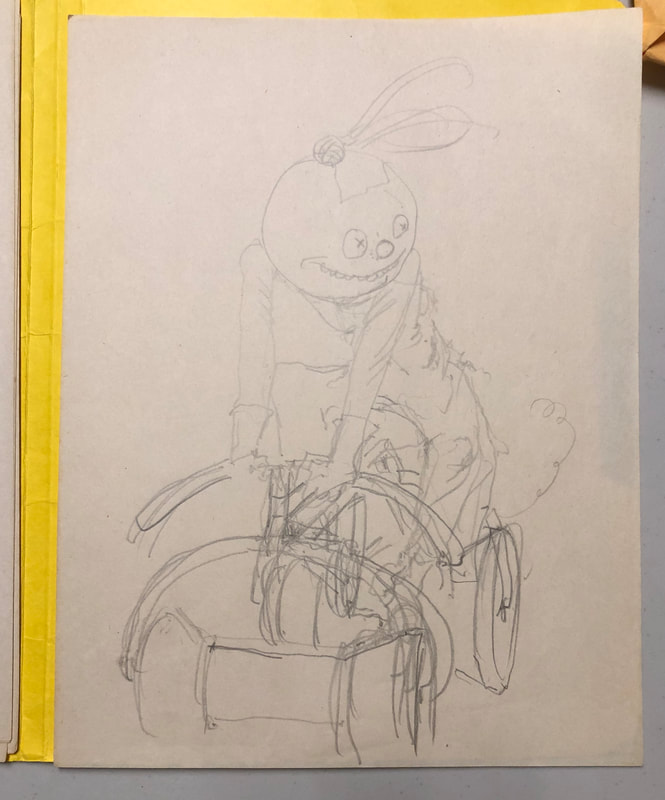

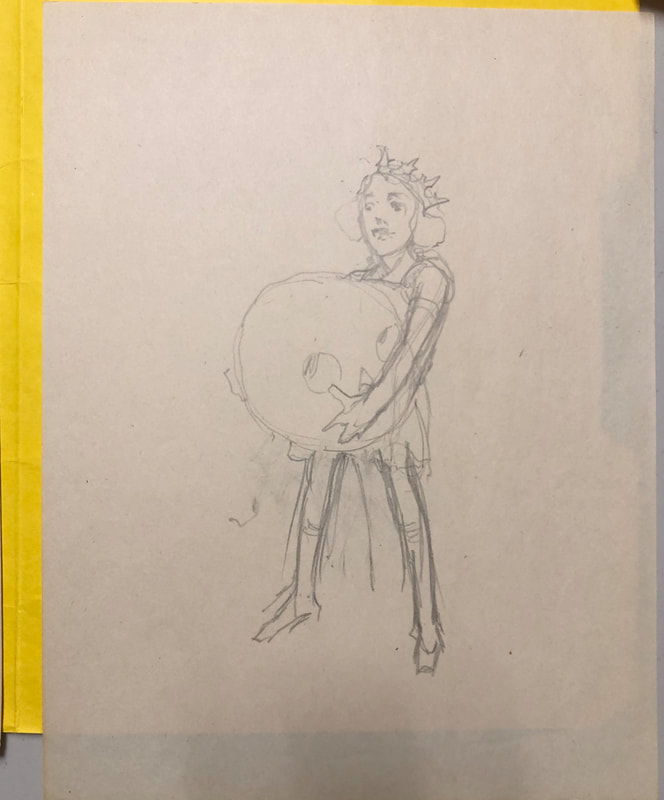

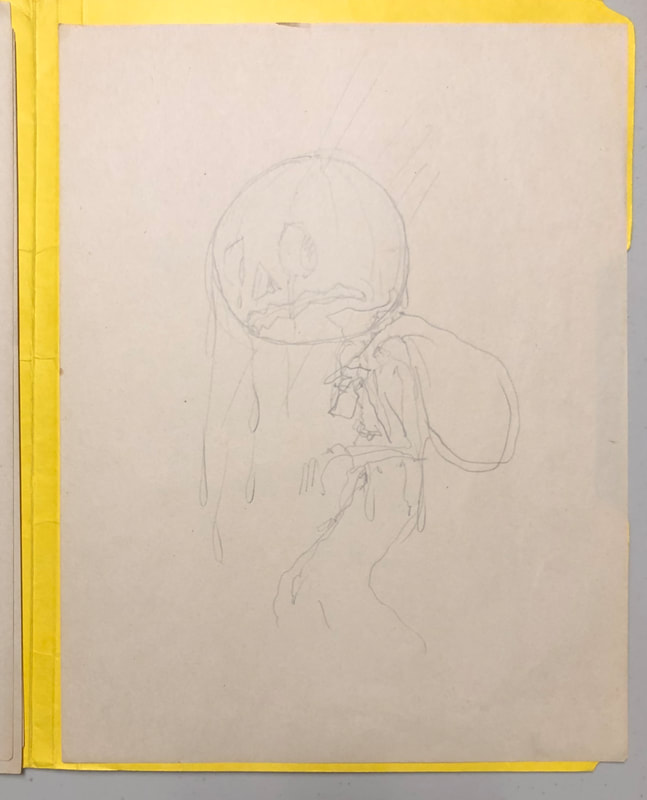

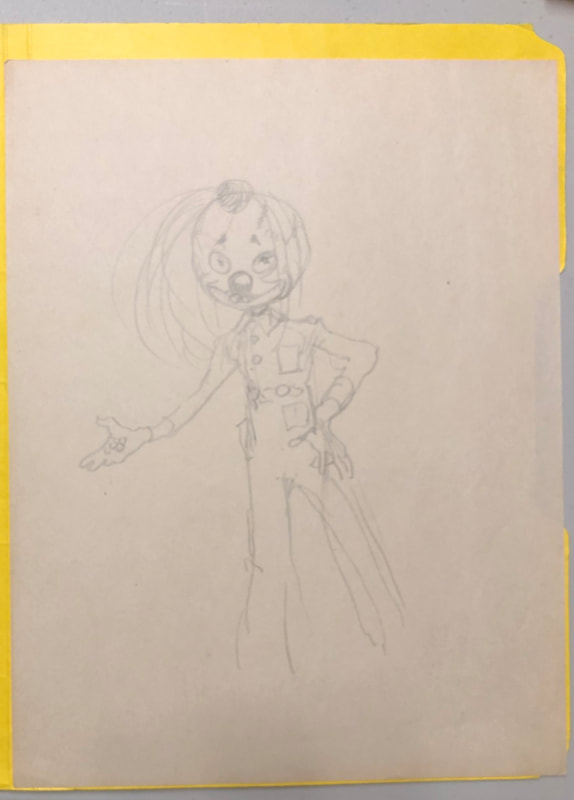

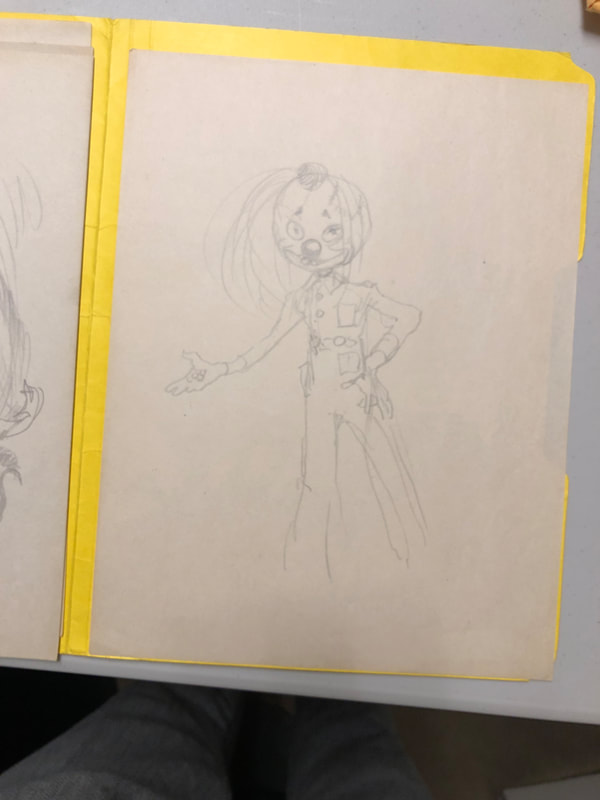

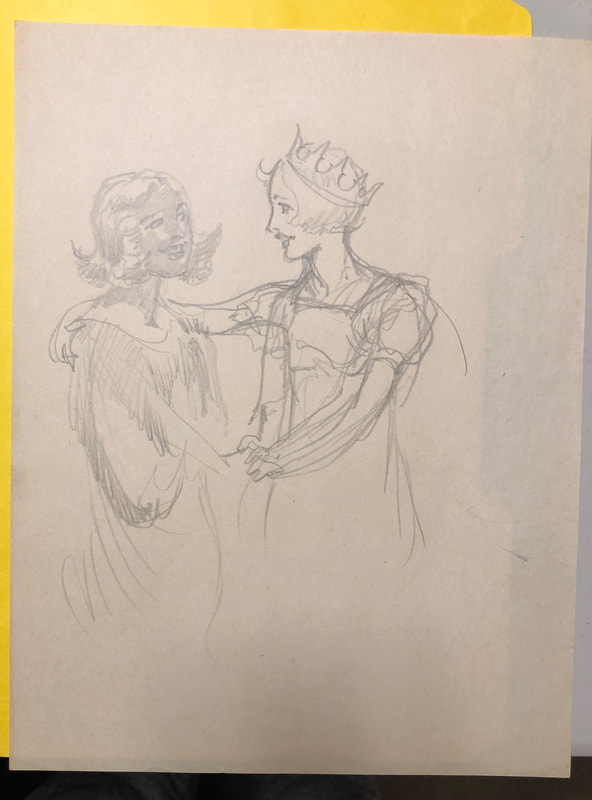

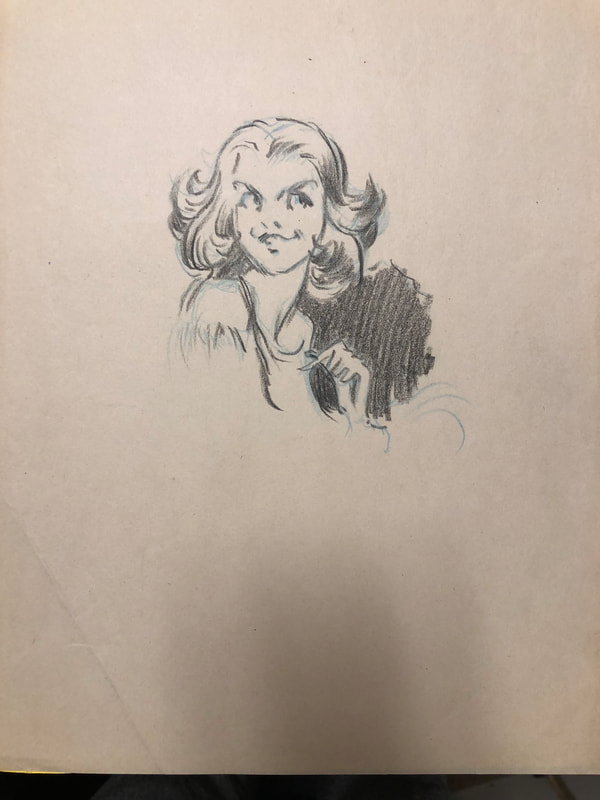

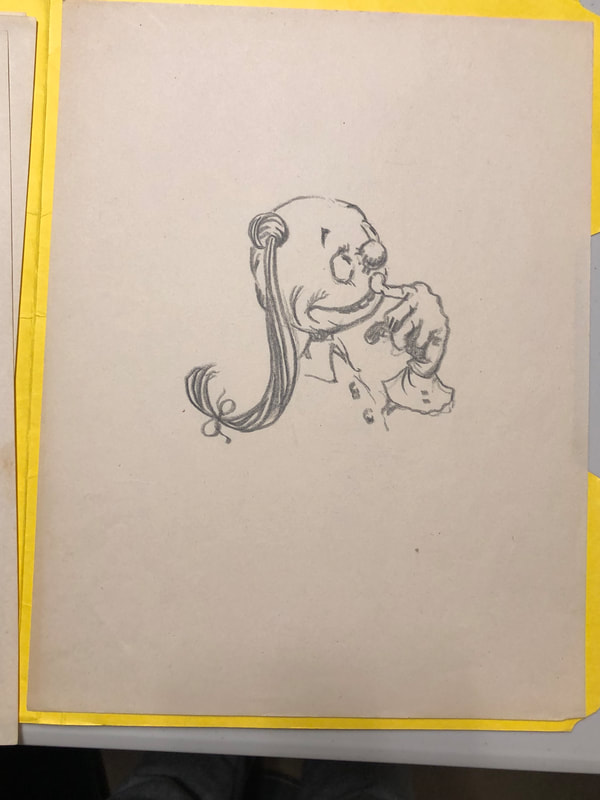

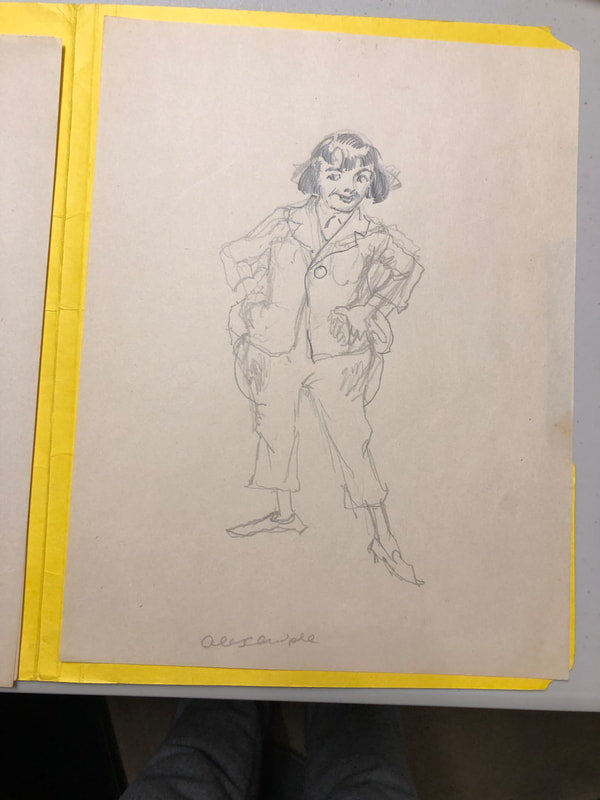

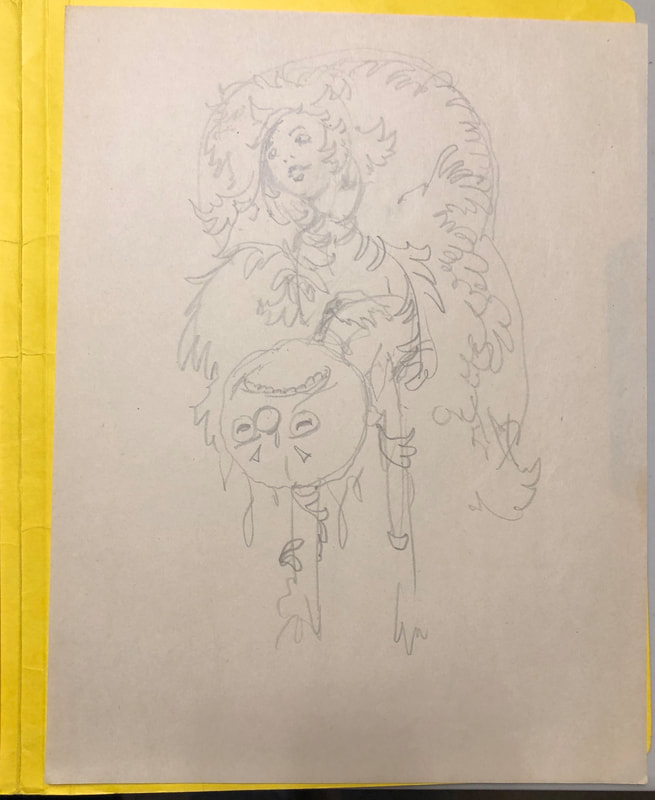

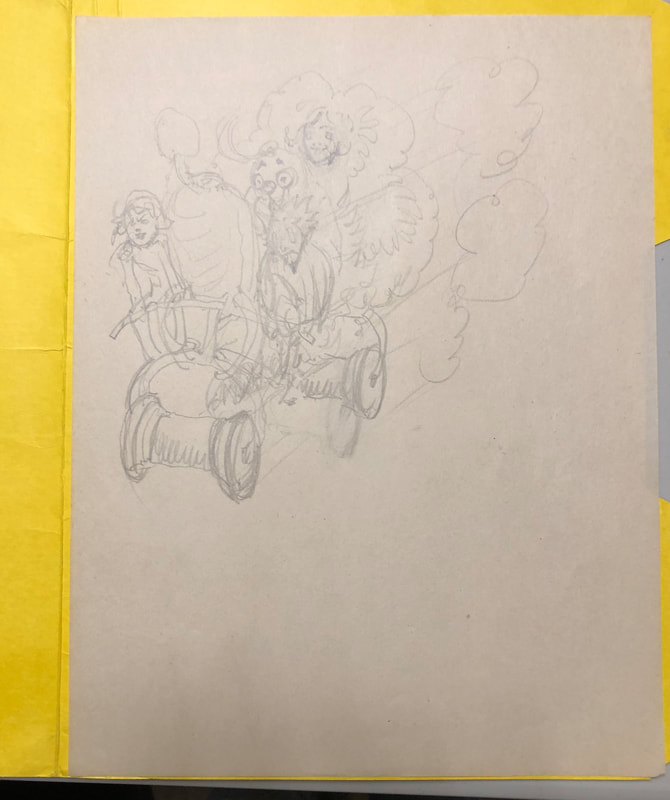

Martin’s new jacket designs for the Oz series were vibrant, inviting, and ultimately short-lived. In 1964, perhaps riding a new wave of Oz nostalgia fueled by yearly telecasts of the 1939 MGM film, Regnery decided to revisit the publication of the Oz books yet again. Narrowing public focus by discontinuing all but the Baum titles in the series, he again asked for the recreation of John R. Neill’s classic cover designs. A brilliant artistic mimic, Martin was assigned the task, and the publication of what is now known as the "white editions" in 1964 helped usher in a new generation of Oz fans, and finally saw the Oz books become staples in the American public library system. Dick Martin retained the original artwork he created for The Visitors from Oz and his dust jacket designs, and perhaps wishing to pay forward the gift he felt in obtaining priceless original Oz art treasures from the Reilly & Lee archives earlier his career, offered them as gifts and to be sold at convention auctions benefitting the International Wizard of Oz Club. Dick Martin would also become the last "official" illustrator of Oz, when Regnery, under the Reilly & Lee imprint, issued one final Oz book, Merry Go Round in Oz by Eloise Jarvis McGraw and Lauren McGraw Wagner, in 1963. This time, the final artwork by Dick Martin would take its place alongside most of the illustrations drawn for the Oz series by his artistic predecessors; likely drawn "for hire," it is now presumed lost as well. Special thanks to Andrea Grimes at the San Francisco Public Library, and to Bill Campbell of The Oz Enthusiast for providing photographs. Dick Martin The Magic of Oz Drawings (BASC 12), Book Arts & Special Collections, San Francisco Public Library  Brady Schwind from "The Lost Art of Oz Project" gives a lecture at ESMoA for "Experience 41: Oz." Brady Schwind from "The Lost Art of Oz Project" gives a lecture at ESMoA for "Experience 41: Oz." Summer of 2019 saw the largest gathering of original artwork created for the Oz book series in well over a decade. The occasion was "Experience 41: Oz," an immersive gallery experience hosted by the El Segundo Museum of Art (ESMoA) in Los Angeles, celebrating L Frank Baum's THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ and its phenomenal pop culture impact. Boasting over 80 original artworks and artifacts from the novel and its inspired stories, ESMOA curated an impressive event that included illustrations by each of the artists who contributed to the original "Famous Forty" series. Highlights included pen and ink drawings by W.W. Denslow for THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ, and works by John R. Neill for each of the Baum titles for which original artwork is known to survive (THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ, OZMA OF OZ, THE ROAD TO OZ, THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ, THE PATCHWORK GIRL OF OZ, TIK TOK OF OZ and GLINDA OF OZ) as well as preliminary sketches for several Ruth Plumly Thompson titles, including HANDY MANDY IN OZ and THE PURPLE PRINCE OF OZ. Illustrations for the Oz books by later artists, Frank Kramer, 'Dirk,' and Dick Martin were also represented. On August 22, 2019, The Lost Art of Oz Project was invited to host a tour of the exhibit. Brady Schwind (joined by expert guests, Jane Albright, the President of the International Wizard of Oz Club, and prominent Oz collector, Freddy Fogarty) regaled a sold out audience with stories behind the pieces on display and from his search to track down the surviving original artwork from the series. The exhibit proved a sensational opportunity for exchange between Oz fans, old and new, and a viable platform to educate on the impact the classic American Fairy Tale continues to have as it approaches the 120 year anniversary of its first publication. Museum curators, Barbara Boehm and Eugenia Torres, along with the entire staff at ESMoA, are to be commended for their efforts. The runaway success of the exhibit will hopefully inspire other museums and institutions to take on the merits of Oz and the enduring impact of its illustrative designs. To view a "Grid" of the works featured in "Experience 41: OZ" visit this link at ESMoA's official website.  Of the nearly 4,000 finished illustrations John R. Neill drew for the Oz book series, less than 10 percent are known to survive. Perhaps surprisingly, most of what does survive is from Neill’s earliest work on the series. Of the 13 novels Neill illustrated for original Oz book author L. Frank Baum, at least one piece of finished artwork is known to exist for 8 titles. Conversely, of the 19 Oz books Neill illustrated for Baum’s successor, Ruth Plumly Thompson, only 5 books have known finished examples. Sadly, this means many of the most vibrant drawings (and the most colorful characters) Neill drafted for the Oz books may have been lost to time. John R. Neill’s family retained none of the final artwork Neill created for the Oz book series (all was turned over to the publisher upon completion) but they did retain many of Neill’s preliminary pencil sketches. Happily, much of Neill's preliminary Oz sketches are for characters and books for which no final artwork is known to survive, and they give us a rare glimpse into Neill’s process, and of the creation of some of the most beloved creatures in the Oz book universe. Neill’s assignment of illustrating the Oz books was often a fast task, and there are frequent stories of his having received the finished manuscript so late, he had less than a month’s time to complete the final drawings before publication deadline. At the top of the blog is an image Neill composed for "Anything of Oz," an anxious attempt to begin work on the yet to be received manuscript of THE GIANT HORSE OF OZ (1928). But Neill’s imagination was readily accessible, and he often began sketching ideas right on the typed manuscripts as he first read them, as exampled by Neill's copy of the manuscript for SPEEDY IN OZ (1934) now housed at the San Francisco Public Library. John R. Neill was an illustrator who frequently used models to capture expression and anatomy. And it's easy to imagine that Neill may have sketched in real time - perhaps even members of his own family as inspiration - for an early design of King Randy of Regalia and Planetty, the name sake of THE SILVER PRINCESS OF OZ (1938). It’s equally understandable that often Neill’s surviving preliminary sketches are for creatures that don’t exist outside the worlds of fantasy. A particularly delightful example are those he drew for a seven armed shepherdess named “Handy Mandy,” one of the most whimsical characters in the entire series. On two pages, Neill attempts to sort out the details of how such a creature would navigate every day movements: running, jumping, pointing, lifting. Perhaps so tickled by his findings, the sketches became the basis for the endpapers of the final book, HANDY MANDY IN OZ (1937) and an inspired introduction for the reader into her unusal world. The only surviving sketches from OJO OF OZ (1933) are for the character Snufferbux the Bear, and they detail another recurring theme in Neill’s preliminary sketches - how to make the ordinary, “extraordinary.” Back to anatomy, Neill seems to first want to master the realistic stance of the animal, then slowly embellishing and animating to create a non human character who speaks and dances. Similar sketches exist for other animals in the Oz universe, and they echo Neill’s desire to first satisfy realism before turning to fantasy. John R. Neill’s finished pen and ink illustrations for the Oz books were usually done on Bristol board. In 1909, while drafting his work on Baum's THE ROAD TO OZ, Neill used one side of the board for rough pencil sketches and the other for a final drawing (usually of a different scene in the book). Some of the most fun surviving examples of these are Neill's early renderings of what Jack Pumpkinhead’s pumpkin house might be, and what the anatomy of the Shaggy Man’s head emerging from water might look like. The last surviving examples of Neill’s preparatory sketches are from 1943 for a book Neill wrote called THE RUNAWAY IN OZ. Neill created an extensive collection of pencil drawings for his ideas of how characters and scenes might look. Sadly, Neill died before the book could be edited or the illustrations finalized. In 1995, Neill's manuscript was revised and illustrated by Eric Shanower, who used Neill’s rough sketches as inspiration for his final drawings. Special thanks to Michael Patrick Hearn for insights and David Maxine, Jory Neill Mason, Bill Campbell and The Oz Enthusiast Blog, The International Wizard of Oz Club, Robert Schmidt, and the San Francisco Public Library for images included in this blog.

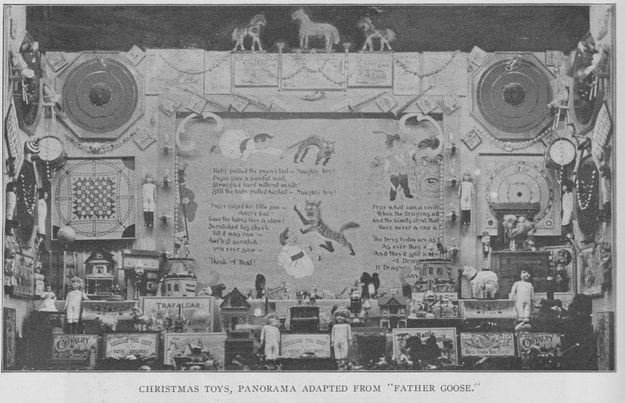

In L. Frank Baum's family scrapbooks there is a tantalizing photograph of a 1904 window display at Siegel & Cooper Co. department store in New York City celebrating the release of Baum's second book, THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ. The exhibit is lavish with detail: first printing copies of the book abound (in what appears to be both green and red cloth variants of the original binding), large doll like figures recreate the book's endpaper design (dedicated to Fred Stone and David Montgomery as the Scarecrow and Tinman from the 1903 stage production of The Wizard of Oz ) and a large poster teases "What Did The Woggle Bug Say? - a much heralded campaign that offered newspaper readers the chance to win weekly prizes. Circling the entire window - on hangers and easels of various shapes and sizes are illustration boards, featuring John R. Neill's original pen and ink drawings for the book. The photograph in Baum's scrapbook is grainy, and it's been a fun and fascinating puzzle to try to guess which pieces of artwork are included. With special thanks to the sharp eye of our friend Bill Campbell of The Oz Enthusiast, we think we've been able to solve a bit of the mystery... Top: Original photograph from Baum's scrapbooks. Bottom: Our estimation of the featured artwork. Can you guess any of the illustrations hanging in the back? Interestingly, none of the illustration boards identified here are among the small handful known to have survived. The caption under the photograph states a similar display was at Wanamaker Store in Philadelphia. For those who love to follow New York 'then and now,' the Sixth Avenue location of Siegel and Cooper Co. is currently the home of Bed, Bath and Beyond; the window display still retaining its original green patina molding Special thanks to The International Wizard of Oz Club for images featured in the L. Frank Baum family scrapbooks.

One of the central fascinations at the center of the "Lost Art of Oz" search is that, with the exception of the artwork created by WW Denslow for THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ (much of which was gifted to the New York Public Library in 1926), all of the original artwork created for the Oz Book series was retained by the publisher, Reilly and Lee. So in looking at what has survived and what else might be 'out there,' the game often becomes trying to determine the 'how' and the 'when' individual pieces started going AWOL from the R&L archive. A common practice for turn-of-the century marketing of children's books was for major retailers to create prominent window displays featuring for-sale books along with pieces of original illustration. Usually oversized and drawn on sturdy Bristol Board the artwork was an easy, eye-popping and inexpensive way to draw young eyes, and publishers were happy to lend them, with the caveat (sometimes honored and occasionally not) that they be returned when the promotion was over. A popular legend in the Oz Collecting world is that a series of original watercolors created by John R. Neill in 1910 for THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ were loaned to Marshall Field & Co., an upscale department store in Chicago, to advertise the book but were never returned, only to be discovered decades later in the company's basement.

Someone else who managed to commission an original piece of Oz artwork from John R. Neill was an impassioned Ohio based radio writer named Jack Snow. Corresponding with fellow Oz collector, Roland Baughman in January of 1942, Snow shares his great pride in obtaining it. The original John R. Neill watercolor in Jack Snow's collection was not from an Oz book, but was later reproduced in the Winter 1986 edition of The Baum Bugle.  Jack Snow Jack Snow So, it's perhaps not surprising that the next known documentation of original Oz series artwork being in private hands would be in a note from Snow. In a January 9, 1947 letter to a collector named William G. Lee (no relation to the publisher), Jack writes: "I have The Land of Oz, first edition, presentation copy in dust wrapper with four original Neill illustrations." Before he was done collecting, Snow would end up with a second first edition MARVELOUS LAND in a dust jacket (which may play a part in our story later on). Despite his passion for Oz, which extended so far as to writing two books in the series (THE MAGICAL MIMICS IN OZ in 1946 and THE SHAGGY MAN OF OZ in 1949, as well as a readers guide called WHO'S WHO IN OZ in 1954) the later years of Snow's life were marked by tragedy and economic hardship. By 1955, he had sold most of his collection to prominent New York dealers Howard Mott and Gabriel Engel. Though it's inconclusive what became of the four original Neill illustrations from the MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ in Snow's collection, it seems likely that three of these (along with the endpapers drawn by WW Denslow for Baum's DOT AND TOT IN MERRYLAND, and 8 assorted 1904 drawings by Denslow for a short lived comic strip based on the characters of The Scarecrow and the Tin Man) were purchased in November of 1955 by Roland Baughman for Columbia University (the subject of our previous blog). The cost for the 12 drawings was $400 (about $3,782 in 2018 dollars) which shows the relative low valuing of the original artwork at that time. A far more impressive price was placed on Snow's two first edition, dust jacketed copies of THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ, which were offered by Mott for $200 each. One of these copies would be obtained by Oz illustrator and collector, Dick Martin. Also in Martin's collection was an original illustration from THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ, featuring Tip admiring the newly formed Jack Pumpkinhead. Across the board is a crack, almost identical to fractures in the illustrations purchased for Columbia University. Could this be the fourth original illustration from Snow's collection? If so, it might be the first piece of original Oz series artwork connected to Dick Martin. It would certainly not be the last, as we will explore in our next blog. Special thanks to Cindy Ragni of The Wonderful Books of Oz, Bill Campbell and The Oz Enthusiast and

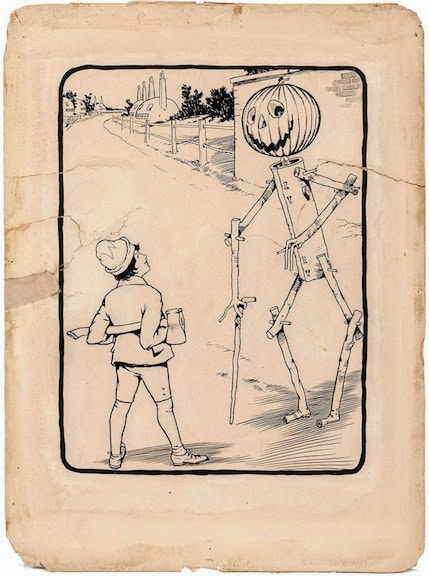

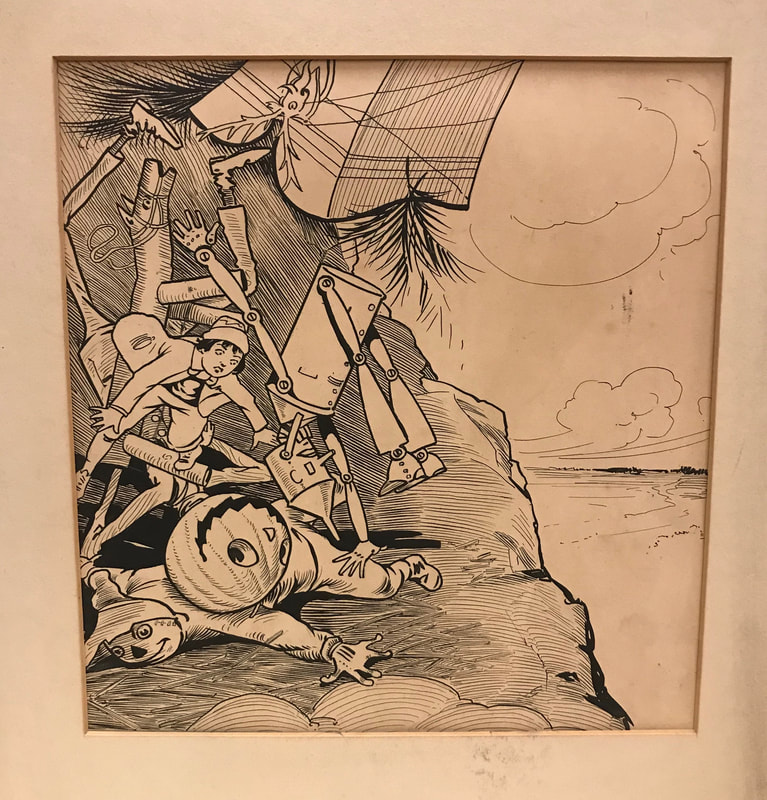

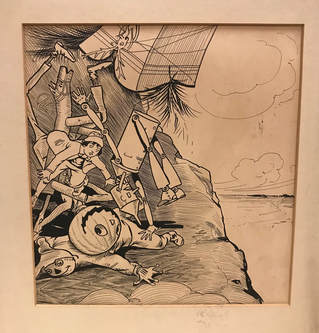

The International Wizard of Oz Club for images featured. The road to tracing the existing original artwork created by John R. Neill for the Oz series is more often than not a scavenger hunt. It starts with a lead, which leads to a lot of inquiry work, and occasionally - just occasionally - results in an undiscovered treasure. Such was the case of a recent search in the vaults of Columbia University. Now, Neill, himself, retained none of the illustrations he drew for the Oz books. They were expressly the property of the publisher, Reilly & Britton (later Reilly & Lee, and later still Regnery and then Contemporary Books). By the time Contemporary sold the last of its Oz archives in the early 1980s, but a tiny fraction of the original artwork was left. It's largely believed most of the artwork was purged by the publisher in the early 1960s, and so it's always intriguing to learn of a collection in private or public hands that pre-dates that time period.  The first major exposition of L. Frank Baum's work was in 1956 at Columbia University, and it was the brainchild of Roland Baughman, who was the Head of the Department of Special Collections at Columbia, and a fervent collector of L. Frank Baum and Oziana himself. The exhibit contained books and a few pieces of original artwork by Denslow and Neill that Columbia purchased specifically for the exhibition. In the decades since the exhibition, the drawings have been housed with the effects of Roland Baughman's papers (gifted to Columbia upon his death in 1961) and as is often the case with Neill's art, misidentified in the school's records. Thanks to the efforts of the dedicated staff at the Butler Library, the works were traced and brought out of the vaults, for what may have been their first viewing in a very long time. Still encased in the inexpensive black wooden frames they were put in for the 1956 exhibit (and covered in decades worth of dust), the three illustrations from THE MARVELOUS LAND OF OZ nevertheless remain- well, absolutely marvelous. The first drawing, featuring Tip and Jack Pumpkinhead sleeping on the side of a hill, while the Saw Horse watches nearby corresponds to the colored plate on page 56 of the published volume. Neill, incidentally, with the exception of his watercolors for THE EMERALD CITY OF OZ and DOROTHY AND THE WIZARD IN OZ did all his works in pen and ink on Bristol Board, with the colorization happening later (and by other hands) in the printing process. This work is especially notable in it's homages to traditional Denslow flourishes; in particular, the outline of a larger than life sun overhead may have been Neill's attempts to mirror the style of his highly successful predecessor on the Oz series. The second sketch of Tip, Jack and the Sawhorse crossing a river is intriguing in that it is the only original art for a half-page sized illustration that is presently known to have survived from MARVELOUS LAND. A fun surprise is seeing that despite the rather small size of the illustration in the published book, Neill took an entire full-sized board to craft the drawing! Neil apparently made some changes to the design of this illustration as there is an 'insert' piece of paper pasted on the middle of the board and drawn over. Both illustration boards unfortunately have major damage to them; large cracks cross the entire length of the image. Interestingly, this damage corresponds to a similar split on another illustration board from LAND sold at auction in recent years, and would indicate the damage may have been sustained in the storing of the works at the publishing house. How the works came to leave Reilly and Britton remains a mystery... The third illustration from MARVELOUS LAND is on a slightly smaller board (and one with a slightly different sheen). Though familiar, there was something instantly 'off' about the image, but it took a moment to realize what it was. When compared to the finished illustration in the published book, something is missing. Can you see what it is? Ah yes! It's our old friend, H.M. Wogglebug T.E., MIA from the pen and ink illustration! But what could that mean? Is this illustration at Columbia a copy? A drawing for an abridgment of the story in which the Wogglebug doesn't appear? Or was this a preliminary drawing done by Neill that perhaps was rejected upon the realization that a major character from the episode was missing?

An early (and persistent criticism) L. Frank Baum had of John R. Neill's work was that he failed to astutely observe the details in his narration. While we may never know what exactly is the story behind it, it seems likely that this was (perhaps the first) instance in which Baum finger wagged his new illustrator for not closely reading his story. |

AuthorBrady Schwind is a writer, director, and Oz Enthusiast on a mission to definitively catalogue the existing original artwork from the famed "Famous Forty" Oz books. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed